Last week marked one month since Chilean president Sebastian Piñera used a dictatorship-era constitutional power to declare a state of emergency in ten out of sixteen regions of the country, declaring war on protesters.

The conflict, which has been superficially described as a reaction to a spike in metro fare in Santiago, has deep roots: economic inequality and disparity between the rich and the poor; a dictatorship-era constitution which severely restricts civil liberties; terrible distribution of social services like health and pensions for the working population; and a pro-extractivist agenda which loots water and the environment for industrial interests.

The events unfolding have likely awed many following the mainstream media (and perhaps even Piñera himself?) at its widespread and unwavering nature. What many of us didn’t see in Canada though, was the brutal, inhumane repression which the state military police “carabineros” have been exercising against protestors across the country. According to the National Institute of Human Rights (INDH) the repression (until November 15th) has resulted in:

- Over 20 deaths

- 217 eye injuries resulting in blindness (most having deliberately been shot in the face)

- More than 2,000 injuries

- More than 6,300 detained

And these numbers are surely underreported. There have also been accounts of sexual assaults of female protestors, and high numbers of youth detained and injured by the carabineros.

Canada’s silence on the issue – especially compared with its immediate reactions to crises in Venezuela and Bolivia –is strategic, and Canadian mining interests might just be at the centre of this decision to turn a blind eye to some of the fiercest repression since the Pinochet dictatorship.

In light of this silence, we interviewed members of communities and organizations in Chile affected by Canadian mining companies to understand how this month-long mobilization is connected to the much longer struggle that they have been waging in their communities – for fairer working conditions, for water, and for life.

“Esto no es Sequía, Esto es Saqueo!” (This isn’t drought, it's plunder)

According to official accounts, Chile is facing the worst drought in recent history. In September, 2019, Piñera decreed a “State of Catastrophe for Drought” for the Atacama, Coquimbo, and Metropolitana regions in the country. Government officials noted that the drought, the worst in 60 years, was the product of climate change.

But, for folks living near industrial extractivist projects, and for organizations like Chile’s National Movement for Water and Territories (MAT, from its initials in Spanish), climate change was merely an excuse that prevented the agricultural and mining industries from being spotlighted for their irrational and unsustainable consumption patterns. Camila Zarate, spokesperson for the movement, told us in September,

“We’re told that the water crisis in Chile is due to climate change. Of course, we have low rains and this is a historic fact, but is this the main source of the drought? …We know that the reality is that the demand for water is simply much greater than the amount of water available. Yet the incentive is to continue extracting water for industrial agriculture and mega-mining.”

Climate change is being used more and more by industry as an excuse to clear themselves of any responsibility they may have for damaging the environments where they work. The Canadian government is also using a similar discourse in defence of mining companies. In August, we met with officials from Global Affairs Canada (GAC) and a member of a Chilean grassroots organization, Putaendo Resiste, facing unwanted exploration by a Canadian junior company. When she spoke of the community’s fears of water shortages in light of the company’s proposed extensive water-use plan for the giant copper mine, the GAC official looked at her and asked “how do you know for sure the company’s activities are causing the drought? I know that the region is already impacted by climate change.”

In Chile access to life’s most vital element, is privatized. Water rights, encompassing or in some cases exceeding the available natural flow, are allocated to corporations that can either sell the water or, in the case of mining companies, use it themselves.

It is also the largest copper-producing country on the globe, with open-pit copper mines pock-marking the landscape in the northern regions of the country. Open-pit copper mines are water hogs and the impact of large-scale industrial mining activities in the North occurs alongside regions already plagued with severe water shortages and desert-like conditions.

In 2018, the Chilean Copper Commission noted that the copper industry consumed 16.25 cubic metres of water per second. This translates into 512 million cubic metres per year, 1.5 times the annual consumption of the 2.8 million people who live in Toronto. The commission predicted that overall water consumption for the industry was projected to increase over the next five years, but that desalinated seawater (now accounting for less than 10% of total consumption) would cushion that increase by eventually accounting for ⅓ of the total water consumed by the industry.

MiningWatch Canada was in Chile at the peak of the dry season and we visited communities in the 5th region (bordering the metropolitan region of Santiago), who spoke with fear and horror about the “approaching desert” from the North. We also spoke to many representatives of communities from the North affected by Canadian mineral exploration and production.

On the ground, the irrationality of such a system, which in some cases requires building pipelines hundreds of kilometres in length to transport fresh water to the mines from areas where shares in this resource are still available, is not lost on Chileans who, at the time of our visit, were getting access to drinking water once every 10 -12 days. The rivers are bone dry, with the water sources already dammed and channelled in order to ensure that the “owners” of the resource receive it without interruption.

As we met with communities affected by a Canadian company, Los Andes Copper’s copper exploration mega-project “Vizcachitas”, neighbours expressed their anguish as reports came back from small-scale herders returning from the mountain range with their herds. Accounts of “50 goats didn’t make it,” and “100 head of cattle, dead,” were bemoaned by the small communities of Los Patos where many families still depend on the centuries-old practice of cyclical grazing. In nearby Putaendo and San Felipe, horses and cattle close to thirst and starvation wandered around separated from their herds and owners, in a desperate pursuit of water.

“Even the highland robust shrubs, which are able to withstand long periods without water, are dying,” expressed one resident as we passed kilometres and kilometres of spiny prickly cacti bushes that were burnt from the fierce sun.

And the problem doesn’t start with the mines themselves; it is structural, and worked into the political and economic fabric of the country’s industries. The controversial Alto Maipo hydroelectric dam megaproject has been called the “emblematic project” in Chile that demonstrates the collusion between economic and political powers in Chile to promote projects which merely benefit the industrial elite at the expense of the majority of Chileans. The mining industry, has been the principal benefactor, according to Anthony Prior, a spokesperson for the Metropolitan Network No Alto Maipo (Red Metropolitana No Alto Maipo). But, he also notes that the struggles on the streets, will not stop, until the most core demands are resolved: “People are in the streets and we will continue to struggle until we reclaim our water as a public good and human right.”

Canadian Mining Companies Contributing to the Extractivist Agenda

There are currently over 40 Canadian mining companies with over 100 mines and projects in Chile. And, Chile is tied for second with Mexico (after the U.S.) for Canadian direct investment abroad in mining, Canadian mining assets totalled 17 billion dollars in 2018. The majority of these are junior mining companies engaging in copper and lithium exploration, but companies like Yamana Gold, Teck Resources, and Lundin Mining also have operating mines in the country, primarily in Copper but also in gold and silver.

Canada is the most important foreign investor in mining in Chile.

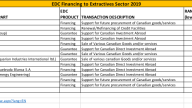

It is also important to understand that beyond Canadian capital investment, there is significant investment from Export Development Canada into Chile. In 2019 alone, EDC invested between 1 billion and 1.5 billion dollars in the extractive sector alone. Their financing activities went directly to large-scale copper mines, like Teck Resources "Quebrada Blanca" expansion project, but they also invested into Chilean owned companies (CODELCO) and BHP's giant "La Escondida" copper mine. Their financing also included companies in the commercializing and trade sector for the extractives industries, presumably to secure access to concentrates exports being imported to Canada (see Data Table attached).

Canada’s silence about the ongoing human rights abuses, therefore, must be understood within this context.

MiningWatch met with communities and organizations affected by Canadian mining companies in September, 2019. We followed up with them, following the initial widespread protests in October, as they were overwhelmingly organizing and joining actions in their communities. They were making links to the protests and their own resistance in their communities to mining. We wanted to make those links known to Canadians. What we discovered is that communities’ concerns about water, environmental contamination, and economic inequality provided the undercurrent for their participation in the nation-wide protests.

The Companies

Los Vizcachitas Project, Los Andes Copper

Los Vizcachitas is owned by Los Andes Copper. The project, in pre-feasibility phase, purports to develop a massive open-pit copper mine, whose pit will sit directly atop the Rocín River (the main source of freshwater for the communities downstream, and upstream of the newly constructed dam), and the tailings facility (for 110,000 tonne/day and 220,000 tonne/day scenarios) on the Chalaco River about 10 kilometres upstream from the Los Patos community.

Putaendo Resiste is an agrupation of representatives of a diverse array of organizations from the Putaendo commune who have been organizing to prevent the exploration and development of this mine upstream from their communities. Their biggest concern is protecting water, an ever-scarce resource, since the Putaendo valley is fed from a nearby rock glacier, as well as protecting their communities from potential contamination or spills resulting from the mining operations given their proximity to the proposed mine site.

They note that between 2007 and 2008 the company was denied a Declaration of Environmental Impact permit due to violations in its drilling process, later in 2015-2017 during another phase of drilling, it was sanctioned for having re-routed the flow of the Rocin River and for using water without the proper permits. Its drilling activities have been irregular and have proceeded without all the necessary permits, but the Chilean authorities have turned a blind eye, instead opting to support the company and allow it to resume its activities.

At present the company is attempting to obtain the necessary environmental licences to proceed with another round of drilling, set to commence sometime this year. Communities denounce that their voices have been silenced in this process.

Puteando Resiste has been present in helping to organize and participate in most of the marches in the commune since the state of emergency was declared a month ago.

They note that they have joined the national protests for many of the same reasons being expressed in Santiago. Their fight against the Los Vizcachitas project is a microcosm of the broader economic and social crisis that Chile is living. They say:

“We are supporting and marching because we are part of that majority of Chilean people who are at the bottom, and we are experiencing that injustice just like everyone else. The economic model that we have is grounded in the super-exploitation of natural goods which in turn generates sacrifice zones with very high levels of contamination where, for those companies, they do not care if they contaminate children or entire families. Mining is one of the most depredatory of economic activities because it consumes high levels of water and destroys our glaciers here in the Los Andes mountain range. The owners of these companies are all within the top 1% of the super-rich, making the crisis not only economic and social, but also environmental. This is why, one of the primary demands of the protesters in all of Chile, is to guarantee the right to access water, and why our fight is one for life.”

Carmen de Andacollo mine, Teck Resources

Teck Resources’ “Carmen de Andacollo”, is one of the company’s three assets in Chile. Over the summer, Teck recently announced a multi-billion-dollar investment joint-venture with Sumitomo Metals at the “Quebrada Blanca” copper-mine. Despite its plans for expansion and a capital-intensive push towards automation, the company is arguing that it is in a financial crisis, and that workers have to bear the burden.

Carmen de Andacollo is an open-pit copper mine which employs 474 workers.

As a consequence, the operations at Carmen de Andacollo have been paralyzed for a month, since workers declared a general strike following a lack of good faith in the bargaining process by Teck. According to the president of the Carmen de Andacollo Miner’s Union, Manuel Alvarez, the union’s most important issues are an increase in wages to come closer to the national average for Chilean mine workers, investments in health services and better conditions for workers suffering “catastrophic” illnesses, and better retirement packages for older workers, among other demands.

Despite the fact that these demands are minimal, Teck is refusing to budge. The union membership overwhelming voted against the company’s proposed agreement on November 14th, arguing that the company is not coming close enough to their just demands. They determined, just two days ago, to “radicalize” their actions by taking over a transitway, in order to force the company to come to the table.

Perhaps the most emblematic of the union’s demands is their request that Teck assist workers in fronting the deductible for what they are calling “catastrophic illnesses”. “Some of our members are suffering from leukaemia; this is a catastrophic illness. We want these comrades to deal with these kinds of illnesses with dignity, since it has such an impact on their lives and their families and the community,” said Alvarez.

Andacollo has been determined by government officials to be a region “saturated with contamination,” suffering some of the highest levels of air pollution in the Andean region, with grave impacts for the health of the local population. The World Health Organization has ranked Andacollo among the top 20 worst cities in Latin America for its ambient particulate matter concentrations, which it says can produce increased risk of heart attacks, respiratory illnesses and cancer. An expertinterviewed about Andacollo’s contamination attributed it principally to the mining operations, noting that mineral transportation via roadways causes dust particles to become airborne.

The Environment and Social Development Agrupation of Andacollo (CMA in Spanish) is an urban collective that has been fighting for the right to a healthy environment in Andacollo for 12 years. They note that they greatest risk the Canadian company poses to their people is to the “health and the quality of life of people...since the mining companies arrived, respiratory illness, cancer and leukaemia have increased dramatically according to local hospital data.”

“Because of Teck Andacollo we live in a state of permanent pollution and social division since we constantly face a series of broken promises on the agreements we have.”

Water is another great concern for CMA. They ask that the company “stop using fresh water for the mine, since because of the drought, the only water we have is being contaminated and wasted,” and that it “invest in water desalination technologies”.

The CMA has been joining the ongoing protests across the country, and note that there is clear overlap between their 12-year struggle and the unrest this past month. The extractivist model, they say, “is promoted in the constitution and enables the “indiscriminate exploitation of natural resources, water and energy without paying heed to the needs of citizens. When citizens raise their concerns, they are beaten for demanding their rights be respected.”

Their message to the Canadian public? “Join us in solidarity and raise consciousness about the environmental problems that Canadian mining companies are producing in Chile.”

Alturas Project, Barrick Gold

“Barrick Gold Miente, Saquea y Contamina!” (Barrick Gold Lies, Loots and Contaminates!)

The Alturas-Del Carmen Project is another one of Barrick’s binational gold exploration projects, straddling the Chile-Argentina border, following the mountain range south from Pascua Lama and Veladero.

According to the Assembly in Defence of the Elki Valley, a multicultural group that has been working formally for six years to defend their glaciers against mega-mining, the biggest threat communities are facing by Canadian mining companies is the possibility of water contamination, since their watershed“is already plagued with shortages”. The other risk, related to the first, is the threat that mining in this region poses to the nearby glaciers.

Here their work is preventative, and members hope that they are successful in preventing their valley, its rivers and its glaciers, from becoming another sacrifice zone.

“The Alturas project is another binational project which contends to be larger than Pascua Lama. This project sits on top of our region’s glaciers which feed our watershed with water, and it is only 10 kilometres away from “El Tapado”, the largest glacier in Coquimbo. 20% of our water in Elki comes from El Tapado.”

When asked whether they had been joining the protests over the past weeks, Assembly spokespeople responded in the affirmative, saying “One of the motivations we have as a group is to put an end to the extractivist development model. This pushes us to work towards the repeal of the Chilean state’s constitution, which continues to use bullets to produce bloodshed of our comrades who today have been tortured and assassinated. This extractivist model has been promoted through the constitution in our territories and is the principal cause of our country’s suffering.”

The communities of the Elki valley demand that “Barrick immediately cease its work in the Elki Valley and leave our territory, since we believe they are an attack on the life of the ecosystem that we inhabit as a community.”

Valle del Huasco, Pascua Lama (Barrick Gold) and Nueva Union (Teck-Newmont/Goldcorp)

One can’t talk about Canadian mining in Chile without talking about the Huasco Valley, where some of the most emblematic battles over the natural environment, between a Canadian mining company and communities opting to choose life and water over mining development, have been a constant reality for over a decade.

The group “Coordinator for Life of the Huasco Valley” has been adamant that their resistance to mineral exploration is a fight for life which includes access to clean drinking water for future generations. Giant Canadian mining companies, Barrick Gold (Pascua Lama) and Teck Resources (Nueva Union), are embroiled in legal and socio-political battles to develop multi-million-dollar mining projects in what are surely some of the future’s most important regions, glaciers.

These community struggles will take centre stage in a follow-up piece to this blog, which looks at how Canadian mining companies are directly contributing to exacerbating the climate crisis by drilling and mining in and around glaciers along the Andean cordillera, some of the only freshwater sources that people have in this region.

Minera Tres Valles, Sprott Resource Holdings

Finally, although we did not interview community members affected by Sprott Resource Holdings’ Tres Valles mine directly, it’s important to include the community’sstatement against the company following the recent and tragic death of a neighbour when he was shot in the back with a firearm allegedly by one of the company’s security guards. The mine, like many of the mines mentioned above, sits atop the Andes mountain range, where many herders have historically taken their livestock to graze and drink over the dry season. On our visit to Chile we heard organizations complain time and again that what were once commonly respected pasture and grazing trails and lands in the cordillera region are now cordoned off by mining companies, restricting passage in some cases, and completely eliminating it in others. Those who have suffered the most have been small-scale herders whose families have engaged in this practice for centuries.

In this statement, as in other cases, the community denounces the company’s lack of clarity on transit zones for communal lands. Clearly, as the drought worsens across the country, passageway to more humid zones is becoming a matter of life and death for herders who depend on the glaciers to feed their herds in the dry season.

Mining is part of the climate crisis problem, so it can’t be the solution.

In September, 2019, MiningWatch Canada, along with the Observatory of Latin American Environmental Conflicts (OLCA, Chile), the Latin American Observatory of Mining Conflicts (OCMAL), War on Want, and the London Mining Network facilitated a 2-day workshop that analysed the relationship between the climate crisis, the energy transition, and mining extraction. The meeting was held in Santiago de Chile since, at the time, Santiago was set to host the 25th Convention of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC COP 25), and was also set to be home to a counter-summit, the “People’s Summit”. In efforts to try and influence the climate crisis debate in Chile and internationally, 26 Chilean and international organizations signed onto a public declaration challenging the key premises of the causes and solutions to the climate crisis.

As mentioned, Chile is the largest world producer of copper, and the second largest producer of lithium, both metals that have been deemedcritical to the renewable energy transition.

Not surprisingly, the mining industry have embraced this view of the energy transition, gladly promoting itself as part of the solution. In Chile, across Latin America, and around the world, communities are already experiencing the guilt and pressure that companies are putting on them: “if you want to save the planet and your grandchildren’s future, you need to let us mine x,y,z metal.”

And so it is urgent and important that producing countries and communities are given space to respond and denounce this trend. Here are some excerpts from the statement (which can be found here):

We recognize...that hidden behind the discourse of the 'energy transition' is a program of economic growth for the Global North which threatens to exponentially increase sacrifice zones under the auspices of guaranteeing the supply of minerals for so-called 'green' technologies. This will come at the cost of the exploitation of our territories and communities, all while intensifying the ecological crisis.

That the recent panic surrounding the climate crisis in the Global North can only ever be understood in the context of the struggles present in our urban and rural communities of the Global South, who have been resisting the intersecting social and ecological crises since the inception of colonialism. This panic cannot impose false solutions or reproduce extractivism.

That the climate crisis, as part of an ecological crisis, is a condition of the capitalist world development model.

We denounce...Any attempt by mining companies to benefit from the climate crisis using deceptive initiatives such as: “Inclusive Tailings”, ‘adoption’ of environmental liabilities, Responsible Mining, Green Mining, Sustainable Mining, Ecological Mining, Clean Mining, Climate Smart Mining, Future Smart Mining, offsetting mechanisms for social and environmental damages, Green Economy and any other concept that seeks to wash its image or perpetuate impunity.

That to date, the “COPs” have failed to provide real solutions to address climate injustice and inequality caused by predatory extractivism. Instead they have, under the pressure of Northern countries, made decisions in the interests of the economic model which is responsible for the ecological and climate crisis.

We will fight…to defend water in all its states as a source of life and to sow, celebrate and strengthen territories free of mining.

Despite the unrelenting protests raging in Chile and the fact that the COP25 has now moved to Spain, Sebastian Piñera continues as its chair. He has yet to answer for the brutal repression he has taken out on his people, who are reclaiming a climate-emergency agenda in their mobilizations. Piñera should not be permitted to continue to hold this position with all of this bloodshed on his government’s hands. A recent statement by the Chilean Unidad Social demands that people act to prevent him from fulfilling this role.

Our Chilean partners want us to inform Canadians that, although the COP25 has been moved, their demands will continue to ring strong in the “Peoples’ Summit”. Chile’s private water system, the drought, and the role of the mining and agricultural industry in it, will be at centre stage. You can find the full agenda of the events here.

Canadian mining companies like Teck have sustainability goals related directly to “reducing energy emissions” to battle climate change. And yet, one cannot help but ask the question, as our Chilean partners have, of “how can Teck lead the battle on climate change, if it is contributing to the ecological crisis? Teck’s mines in Chile, and surely its controversial, enormous Frontier tar sands project, speak louder than any sustainability statement can.

The protests, now entering their fifth straight week – and the ongoing repression – are a concern for all Canadians concerned about the climate crisis. Solutions here cannot be built on the back of sacrifice zones in the South.

MiningWatch Canada and our Chilean partners are currently looking for journalists interested in covering the Peoples’ Summit. If you are interested in covering a related story, would like more information, or would like to interview some of the organizing organizations, please contact Kirsten Francescone ([email protected]).