The Trudeau government has finally presented draft legislation to reform the federal environmental review process. Since the new process is being presented as innovative and radical, but also aimed at promoting investment and “certainty” for corporations, it shouldn’t come as much of a surprise if it fails to deliver on promises of evidence-based decisions, promoting sustainability and combatting climate change, and respect for Indigenous rights.

It’s hard to respond definitively to a legislative package that’s 412 pages long, including the Impact Assessment Act, the Navigable Waters Act, and the Canadian Energy Regulator Act, but perhaps some of the energy that went into developing snazzy social media promotions should have been spent making sure the draft legislation will actually achieve its stated objectives.

As noted by other observers (check out the Twitter traffic and various analyses – including excellent ones from Meinhard Doelle and the Canadian Environmental Law Association, among many others), much depends on whether the draft legislation can be effectively amended to bring it closer to its own objectives (nicely laid out in an attractive handbook), and what the key regulations look like (public consultation has already begun for the Project List (Regulations Designating Physical Activities) and the Information Requirements and Time Management Regulations).

As it stands, the government could well be accused of being interested in a process that will allow it to check all the right boxes (climate change and indigenous rights and sustainability and gender etc.) without actually opening it up to meaningful rigour and depth of analysis. In this sense, the worst outcome for both sustainability and democracy would be a process that gives the government adequate credibility with enough specific sectors of the public to allow it to make and enforce decisions that may have nothing to do with sustainability and evidence, or climate commitments, or environmental protection, or Indigenous peoples' rights and livelihoods.

There are a number of aspects of Bill C-69 that are laudable in their purpose, but will require close attention to their wording and implementation (in policy, regulations, and guidelines) in order to be effective. Gender-based analysis, the treatment of knowledge and evidence (both scientific and traditional Indigenous), complete and open information registries, the use of strategic and regional assessments and an emphasis on cumulative effects, collaboration with Indigenous governments – these are all promising commitments that do not appear to be clearly and fully implemented in the draft law.

There are also a number of clear failures. The “lost protections” on water bodies that were supposed to be restored to the Fisheries Act and the Navigable Waters Act don’t actually extend to environmental assessment, or impact assessment, or even just regulation. It’s not at all clear that the government will even require a permit and a registry entry for all potentially ecologically damaging projects.

Likewise, it’s great that the government is putting an end to the frustrating spectacle of the National Energy Board (now the Canadian Energy Regulator) and the Canadian Nuclear Safety Commission pretending to do environmental reviews, as they have since CEAA 2012 gave them this responsibility despite their lack of independence and competence in running public processes. But Bill C-69 introduces a strange hybrid: review panels that are required to have at least one member named by the primary regulator of the project – and makes it worse by adding the offshore petroleum boards to that list.

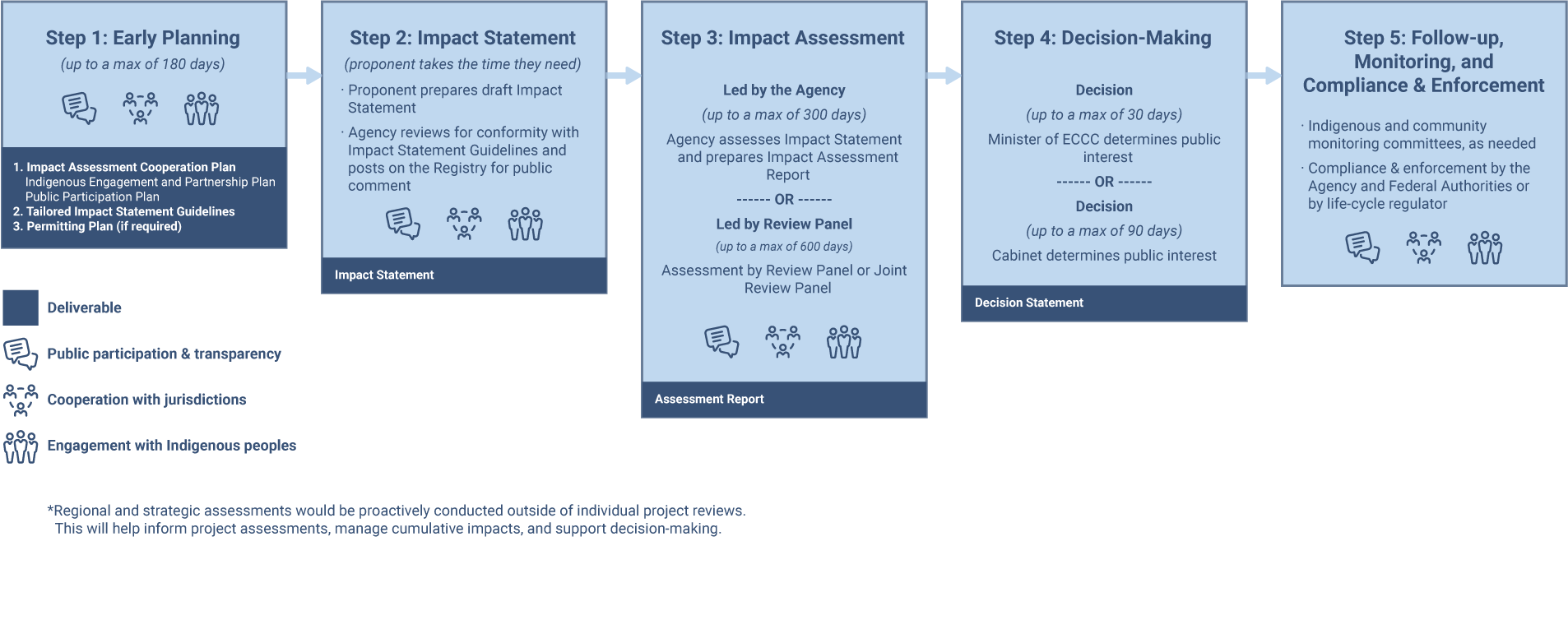

Also in the failure column is the continuation of legislated timelines. Proponents love them, principally because they don’t apply to them. A company can take years to submit its information – and some do – while the public, Indigenous peoples, and government agencies, are stuck with deadlines that don’t take into consideration holidays, weather, or seasonal economic and cultural activities. Timelines are important for proponents and intervenors alike, but they should be set out in guidelines to allow for some flexibility, and there need to be time limits placed on proponents as well. If a proponent drags out a review process too long, the process should be automatically closed, not just suspended.

C-69’s criteria for decision making are also problematic, mostly because there aren’t any. Contribution to sustainability, adverse effects and mitigation, impact on Indigenous rights, and climate change are all merely considerations. There is no attempt to set out criteria at the generic or to require them at the project-specific level.

While it’s kind of cute to say that you must be on the right track if people on both sides of the issue are mad at you, the fact is that sometimes there’s actually a right way and a wrong way to do things.

In this case, for example, you may say you want to make decisions based on sustainability, but if you fail to set out actual sustainability criteria and hard limits on trade-offs (no, you don’t get to destroy that glacier just to make some money, for example, even if you are going to hire only disadvantaged local youth to do it), you end up with the same old self-interested decisions. You can include broader factors in your impact assessment – social, cultural, economic as well as ecological – but with nothing to restrict the political decisions at the end of the road, you effectively lose even the limited existing environmental “significant adverse effects” test.

To be fair, the government is proposing to make those decisions much more transparent and accountable, not by handing them over to an independent commission or tribunal, but by providing public reasons for decisions. And to be fair, if the law were well written and properly implemented, this would be a big step forward. But taking into consideration a bunch of important things in making a decision is not the same as following defined criteria and conditions.

In a nutshell, C-69’s top-line principles and commitments are laudable, but their execution falls short. Whether that gap can be closed through the Parliamentary amendment process, and whether the government actually wants to close that gap, remains to be seen.