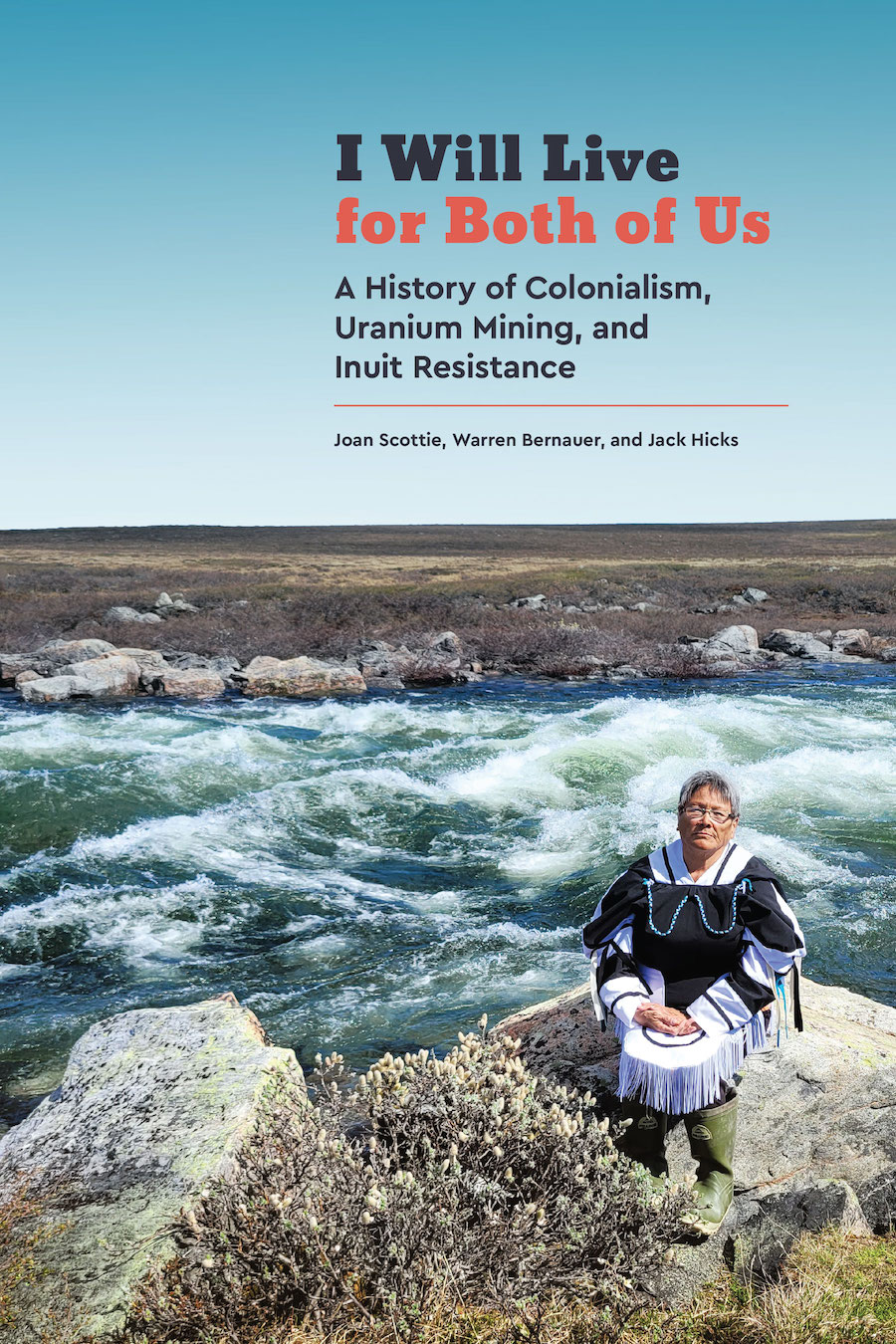

Reviewed: I Will Live for Both of Us: A History of Colonialism, Uranium Mining, and Inuit Resistance by Joan Scottie, Warren Bernauer, and Jack Hicks, University of Manitoba Press

The caribou are life. The existence of the “caribou Inuit” of the Eastern Arctic is inextricable from that of the great barren-ground caribou herds, yet just as Inuit have had to fight Canada’s imposed genocidal policies, they have had to fight to protect the caribou their lives depend on. This unique and important book combines Inuk lead author Joan Scottie’s personal recollections and reflections with documentation and analysis from qablunaat scholar co-authors Jack Hicks and Warren Bernauer to create a perspective that is at once deeply personal but also interlaced with scholarly documentation, bringing new light on Inuit resistance to colonial imposition, whether directly from the Canadian government or from transnational mining corporations.

Joan Scottie tells her own story here, about growing up on the land, and about the richness and hardships of that life, but she is also very frank about the treatment of women and how people suffered and tried to overcome suffering. The title of the book is a powerful statement of what the death of her sister – and the context it happened in – meant to Scottie. This is rich and important story-telling, but it is also crucial to understanding the rest of the book, not just in terms of Scottie’s own commitment to protecting the caribou and the land, but also the larger struggles of Inuit to protect the caribou and to assert territorial authority.

Most Canadians probably know that the territory of Nunavut has existed since 1999, and many know that its creation was part of the settlement of a legal claim by Inuit to reclaim authority over their own territories. What few know is where and how that process started, with Inuit efforts to protect the great herds of barren-ground caribou, and especially their critical calving grounds, from uranium exploration and mining.

The book follows the explosion of uranium prospecting in the 1970s that provoked Inuit to try to stop the incessant drilling and helicopter flights that were disturbing the caribou, through to the Baker Lake Supreme Court decision that eventually led to the Nunavut land claim process. Here Scottie’s descriptions of traditional Inuit understanding of the caribou provide a real insight into how vitally important this struggle is, but also how fundamentally different the Inuit worldview is from that of the mining companies or the colonial government. Inuit tradition, Scottie tells us, is to be extremely careful around caribou migration routes and especially water crossings, taking care not to leave anything whose sight or scent could spook them. The contrast with the prospectors’ attitudes could not be greater – setting up operations wherever it’s convenient, leaving garbage and fuel drums all over, and even buzzing the caribou from the air.

Bernauer and Hicks’ contributions provide a more formal compliment to Scottie’s story, giving shape to the legal and structural changes of the negotiation and implementation of the Nunavut land claim, and the two threads, the personal and the political, as it were, combine to create a compelling picture of the land claim process, the ideals and interests it embodied, and the institutions that it created, including the critical contradictions and shortcomings that are still present. The land use plan that was supposed to be a cornerstone of decision-making is still not in place; the co-management bodies and governance structures are still too often ineffective, and there is visible industry capture of regulatory agencies.

All of this is discouraging, and Scottie confronts her disappointment and disillusionment, but does not allow it to stop her efforts to protect the caribou and to organise and support her community to reject the proposed “Kiggavik” uranium mine not once, but twice. This struggle is the core of the book, and the details are compelling and revealing, both of the community dynamics and of the institutional contradictions, where regulatory protections, planning and environmental assessment processes, and Inuit self-government institutions all serve the community’s interest only with immense effort from Scottie herself, the hunters and trappers, some key Inuit leaders, and yes, the support of activists and outside organisations, including – full disclosure – me and my organisation, MiningWatch Canada.

This book is a fascinating look into a little-known struggle, presented in a format that is deeply personal and emotionally engaging, but also analytical and informative. The specific political and institutional critiques are crucially important to anyone working in or trying to understand the part of the Arctic claimed by Canada. At the same time, the underlying personal, community, and political dynamics, and the struggle to navigate multiple layers of contradiction – the imperative to protect the caribou, the imposition of colonial governance and industrial development, and the negotiation and implementation of the Nunavut land claim – will be of deep interest to a much broader audience, carried by Scottie’s compelling personal story.