Local officials and the Canadian company say no spill occurred. However, affected communities worry about health impacts as no conclusive cause for the dead fish downstream of the Veladero mine has yet been identified.

It’s not easy living downstream from one of the largest industrial mines in Argentina — especially when that mine is the site of one of the worst mining-related environmental disasters in the country’s history. When the communities of Jachal and Iglesias in northwestern Argentina learned from local fisherpeople about the mass mortality of thousands of pejerrey (silverside) fish near Barrick’s Veladero mine in early November 2025, their first thought was that there had been another spill from the mine, says Saúl Argentino Zeballos, spokesperson for the grassroots citizen group Asamblea Jáchal No Se Toca (Hands of Jáchal Assembly).

On Monday, November 3, 2025, after receiving information from worried local residents, members of the Asamblea visited a site near the shore of the Cuesta del Viento dam to document and publicly report about the hundreds of silverside fish that had turned up dead. The dam receives waters flowing from the Veladero mine owned by Barrick Mining Corporation (ABX-TO) and Shandong Gold.

The discovery of the dead fish has caused great concern among the population. As one citizen told a local newspaper: “We know that when something alters the quality of the water, the first to suffer are the small fish. That is why we believe it is urgent to investigate. If something killed those fish, the population may be at risk, because we drink that water.”

About half of the population of Jáchal (approximately 25,297 inhabitants) lives in the urban centre, while the other half lives in rural areas that rely on water from the Jáchal River basin to irrigate crops and to provide the drinking water they draw on through wells. These communities live near multiple mining projects, including the Veladero mine, which has a long record of environmental contamination.

On September 13, 2015, a spill caused by a valve failure in a leach pad pipeline at the Veladero mine released millions of litres of water contaminated with cyanide, mercury, and heavy metals into local watersheds, polluting at least five rivers. Yet the public didn’t learn of the spill until days later, when a concerned Veladero mine employee blew the whistle by sending a message via WhatsApp to alert local citizens. Since then, repeated spills of toxic chemicals at the Veladero mine have been exposed and systematically documented by the Jáchal No Se Toca Assembly. None of these spills was reported by local authorities or the company. In all cases, they were initially denied, and in the first three cases, they were not confirmed until authorities were faced with undeniable evidence, which has created an atmosphere of mistrust among residents toward local authorities and Barrick.

In 2022 and 2023, Barrick responded to UN experts’ official letters raising concerns about the spills by denying any responsibility, saying “any suggestion of spills is baseless and unsubstantiated.”

Inconclusive Reports

Barrick has denied any involvement in the deaths of the fish, stating in local media on November 4, “We want to reassure all residents that Veladero is operating normally and that there is no link between the fish found in Cuesta del Viento and the operation of the mine, according to recent environmental monitoring data [our translation]”. The company did not present any analysis to support this claim at that time.

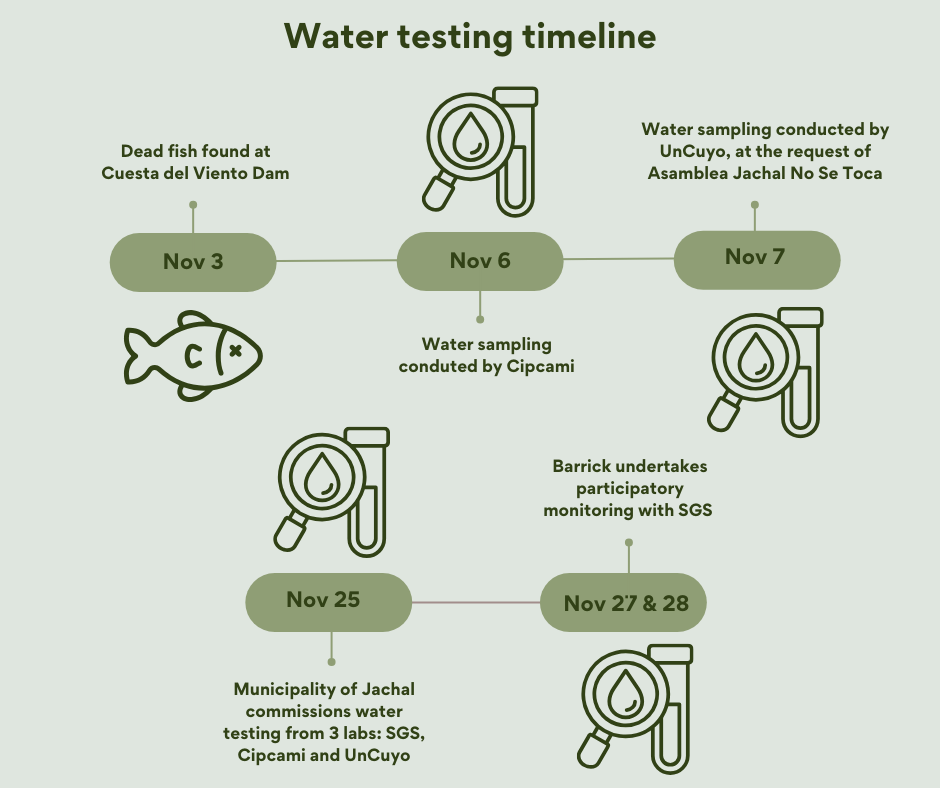

One of the theories initially put forward by local authorities to explain the deaths of the fish was that it was due to natural phenomena. On Thursday, November 6, the Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development of the province of San Juan informed the community that “Preliminary evidence indicates that the event is associated with natural conditions in the body of water, specifically low levels of dissolved oxygen (hypoxia) in coastal areas with poor circulation and accumulation of organic matter.”

However, in an analysis carried out by the University of Cuyo (UnCuyo) on November 7 at the request of the Jáchal No Se Toca Assembly, specialist engineers investigated the conditions of dissolved oxygen in the water in different sectors of the Cuesta del Viento Dam. In a statement about the results of the analysis, the Asamblea affirmed that the specialists determined oxygen levels were not to blame for the high levels of fish mortality since “the measurements taken vary between 7.84 mg/l and 9.16 mg/l, which are optimal levels of dissolved oxygen for silverside.” The fish can survive with levels of dissolved oxygen as low as 6 mg/l.

Another explanation promoted by local media pointed to an alleged low water level in the dam. However, as reported by local newspaper Diario Tierra Viva, “just a couple of months before the phenomenon began, the San Juan Secretariat of Energy Resources had reported that the Cuesta del Viento Dam had 3.45 metres more water—above sea level—than at the same time last year.” Zeballos adds: “In 2024, there were no dead silverside, and now there are; therefore, the recent fish mortality does not appear to be due to the amount of water in the dam.”

The UnCuyo analyses from November 7 also demonstrated that the waters of the La Palca River, which flow from the Veladero mine and feed into the Cuesta del Viento dam, were contaminated with mercury and chlorine. According to Zeballos, one of the lessons from 2015, when the first spill at the Veladero mine dumped a million litres (264,000 gallons) of cyanide solution into nearby rivers was that chlorine “only appears in mountain rivers when hypochlorite is used to ‘neutralize’ cyanide after a spill, just like Barrick did after the 2015 spill.”

Following the Veladero mine spill in 2015, a Safe Water Ordinance was implemented, requiring the municipality of Jáchal to periodically test the waters of local rivers and drinking water for hazardous substances. This ordinance has not been complied with since 2023, so there were no more recent studies to compare with the results taken on November 6.

Twenty-four days after the fish kill was reported, Barrick conducted its own analysis through SGS — a testing, inspection, and certification company that also works with Barrick Gold at its controversial North Mara mine in Tanzania — in what the company calls a “participatory monitoring” process. The company states on its Spanish-language website that “Veladero reaffirms, with verifiable data and processes, that the operation is functioning normally and that there is no link between the fish found in the Cuesta del Viento Dam and the mining activity, located more than 110 kilometres from the reservoir. Based on this, we once again reject the dissemination of unverified, biased information and unjustified assumptions with the sole aim of affecting the peace of mind of local residents and harming mining activity [our translation].” According to SGS, the results for mercury, cyanide, and chlorine, among others, were below the detection limit, adding that “they are within the normal range.”

Following social pressure, the Municipality of Jáchal commissioned simultaneous sampling by three laboratories: UNCuyo, SGS, and Centro de Investigación para la Prevención de la Contaminación Ambiental Minero Industrial (Cipcami) – an agency of the San Juan government. However, like the analyses carried out by Barrick, the samples ordered by the municipality were not taken immediately after the dead fish appeared, but more than 20 days later. Specialists in water, geology, and biology from the province of San Juan consulted by the local news agency Diario Huarpe say the length of time between when the mass fish deaths were reported and when the testing was undertaken can compromise the results obtained. For this reason, the analyses carried out by Cipcami on November 6 and by UnCuyo on November 7, at the request of the Jáchal Assembly, appear to be the most reliable according to local specialists, as they were carried out only five and six days after the fish died.

Credit: MiningWatch Canada

When the Jáchal No Se Toca Assembly went to the prosecutor's office on November 11 to file a complaint about the fish deaths, they were notified that Prosecutor Sohar Aballay of the Northern Prosecutor's Office (Jáchal) had already initiated a criminal investigation on November 5 for the crime of water poisoning at the Cuesta del Viento Dam. The Secretariat of Environment and Sustainable Development did not disclose that this investigation was underway.

The Assembly has also expressed concerns about the omission of a key water sample taken by Cipcami in the La Palca River on November 6, 2025, which was not among the documents submitted by the agency to Prosecutor Sohar Aballay, as part of the ongoing investigation into water poisoning. This sample was taken at the same location where UnCuyo collected water for testing on November 7, 2025. The Assembly’s spokesperson, Saul Zeballos, says that citizens are questioning why this sample was left out, leading to suspicions about whether Cipcami is attempting to conceal evidence from the Jáchal court investigation.

According to Daniel Flores, biologist and professor of geology at the National University of San Juan, fish deaths on this scale cannot be a fluke. “This is not accidental, it is causal... Something caused the mass death, and we must identify what it was. The investigation cannot be left with partial explanations,” he said in a statement to local media.

Three months after the mass death of thousands of silverside fish in the Cuesta del Viento Dam, it remains unclear what killed the thousands of fish: was it a natural phenomenon, or another toxic spill that has not been reported by Barrick?

What is clear is that there are more questions than answers, and that since 2015, there’s no trust towards the Veladero mine.

As pointed out by a local resident who has lived in the area for nearly 30 years, Barrick “has a history of lying, and if they lie again now, what a surprise that would be.”

Intimidation of Environmental Defenders in the Asamblea de Jachal

The Assembly Jáchal No Se Toca has denounced this environmental incident as part of their decade-long struggle to defend water, glaciers, and fragile ecosystems such as the San Guillermo Biosphere Reserve (RBSG) from large-scale mining activities, and systematically document and denounce toxic spills at the Veladero mine and the response (or lack thereof) from the government and Barrick.

As a result of their political oversight and environmental advocacy work, members of the Assembly have faced intimidation and defamation for years. More recently, tensions have been increasing, and the intimidation tactics against the Assembly’s members have been ramping up since they first publicly reported on the death of the fish and demanded that “Governor Marcelo Orrego and the provincial government tell the truth about what happened with reliable and credible technical evidence.”

These tensions came to a head recently when members of the Assembly were targeted in a smear campaign in a pro-mining local media outlet, Diario el Cuyo. The newspaper accused Saúl Argentino Zeballos “leaking the [water test results] to the national media even before UNCuyo had approved it,” which Zeballos denies. In addition, the Assembly has been subject to scrutiny over its financing, which the same media outlet has called “opaque.”

“When they cannot explain the fish deaths caused by mining spills, the San Juan government uses the Diario de Cuyo newspaper to defame the Jáchal No Se Toca Assembly and lie about the cost of the water analyses that the Assembly had carried out with the National University of Cuyo,” says Assembly member Faustino Esquivel.

MiningWatch has obtained a copy of the November 7 UnCuyo water testing report, which is available upon request.