Looking back at Canada’s history with mining

By Joan Kuyek

When MiningWatch Canada started up in 1999, we all hoped that our work would challenge the industry-dominated discourse about mining and smelting in Canada.

We were determined to see academics, journalists, and popular publishers expose the enormous externalized costs of the metals extracted in this country to workers, indigenous peoples, the ecosystem and communities – to see that this is an industry that makes its profits from terrible and often permanent loss.

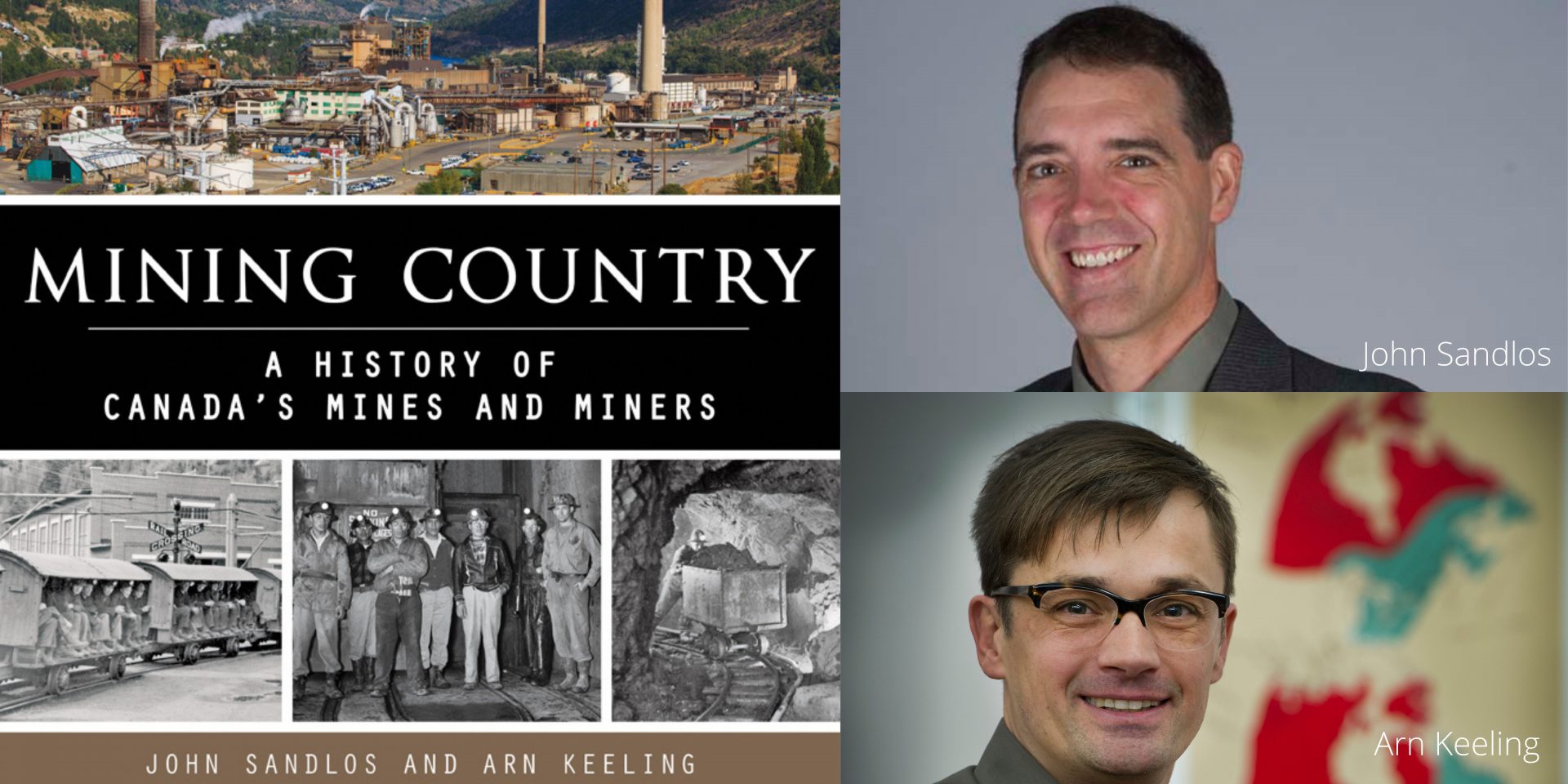

Mining Country, by John Sandlos and Arn Keeling (in paperback, 224 pages, published by Lorimer) is an exciting fulfilment of this hope. The book is a large-format, popularly-written history full of stunning archival photos and well-researched, clear examples of mining conflicts and impacts. The story it tells shows the costs.

The book opens with a description of the Indigenous mining in Canada which preceded colonialism, followed by the march of colonial extraction across the country, including stories of coal and iron deposits in the Maritimes. We hear vivid descriptions of the Marmora/Hastings County, Fraser-Cariboo, and Klondike gold rushes, their impacts on the First Nations they dispossessed and impoverished, and of the miserable (and often short) lives of the miners.

Throughout the book, the authors tie the history of Canadian mining to global trends and events: massive industrialization from 1880 onwards, the Second World War, the post-war construction boom, and neo-liberal globalization. It ends with reflections on the new “green infrastructure” demands for more metals.

The astonishing growth of mining towns like Sudbury, Noranda, Trail, and Cobalt are explained, including the huge price paid by the miners who were maimed and often killed in large numbers. The contaminants spewed by the smelters poisoned land for miles around. The communities where the miners lived were badly planned, poorly constructed, and unhealthy, sometimes leading to typhoid epidemics.

Unions were fought for and eventually won, and some of these struggles are told in detail.

Stories about Yellowknife’s Giant mine, the Westray disaster of 1992, the Asbestos strike of 1949, and the Pine Point mine draw us into seeing the consequences of an unimaginable lack of government oversight coupled with enormous government subsidy. The history of uranium mines in Ontario, Saskatchewan, and the Northwest Territories is compelling.

The book ends with a discussion of the long-term, often perpetual, impacts of mining on the environment and on all of us, and a call to decide if “the endless growth of mineral extraction can be maintained into the future.”

As someone who has spent most of my life living in Sudbury and studying the Canadian mining industry, I found I was a bit jealous of the resources that Keeling and Sandlos have at their disposal – many skilled and enthusiastic graduate students, and sizeable research grants. At the same time, these student researchers are barely acknowledged in the book.

We have no idea who dug up the information that the authors put forward. For example, Mick Lowe wrote a very thorough book on the discovery of Voisey’s Bay which is not even mentioned in the text, although it is in the bibliography. The publisher and the authors appear to have decided to limit the use of references and of a useful index in order to make the book more accessible to the public. For those of us who would like to know where the information came from or to follow up on the stories, this can be frustrating.

This is also a book written by men about men. The endless hours of labour that Indigenous women, miners’ wives, and female community organizers put in to deal with the social, economic, environmental, and health impacts of mining are not even mentioned. The only woman who gets any real attention in the book is the infamous Peggy Witte (now calling herself Margaret Kent), the last owner of the Giant mine. A women’s history of mining in Canada remains to be written, but a good place to start would be Meg Luxton’s excellent study, More Than a Labour of Love, written in 1980.

The book similarly pays little attention approach to the endless work – both paid and unpaid – done by Indigenous and non-Indigenous people to strategize and protect their communities and ecosystems from the mining industry in this country.

In the same vein, I also have to confess to really wincing at the number of times the authors talk about the regreening of 3450 hectares in Sudbury, but fail to mention that the area is considerably smaller than the growing and toxic tailings impoundments that loom over the region and will require care in perpetuity.

Despite these limitations, this is an important and very readable book. It is well-researched and reliable. The photos are stunning. Its excellent labour history will appeal to miners and their communities. The devastating impacts on indigenous people is a story that needed to be told. It does indeed “provide a mining history for all Canadians.”

Joan Kuyek is an author, community organizer and researcher living in Ottawa. She was a co-founder of MiningWatch Canada and continues to support communities affected by mining. Before moving to Ottawa, she was a community organizer and facilitator living in Sudbury.

This review was originally published in Alternatives\Journal. Get Mining Country: A history of Canada’s mines and miners through your local independent bookseller, or order directly from the publisher.