Living a stone’s throw from Barrick Gold’s Pueblo Viejo mine, the largest gold mine in Latin America, communities in the Dominican Republic have good reason to be concerned.

Yearly, the Canadian mining giant extracts over 700,000 ounces of gold at the open-pit mine, dumping mine waste into the adjacent El Llagal tailings impoundment. Fifty-two million cubic metres of toxic sludge – a mixture of waste rock, heavy metals, possibly chemicals like cyanide, and contaminated water – is being held back by a tailings dam roughly 30 stories tall. Built in 2012 in an area prone to earthquakes and heavy rainfall, the dam is nearing full capacity.

Affected communities have long pointed out that Barrick is failing to address or remedy longstanding environmental and health impacts from its current mining operations. Now, Barrick has announced plans to expand its operations and to build a second tailings impoundment that would be two and a half times larger than the existing tailings impoundment and would extend the mine’s life by at least 20 years.

In its March 2023 Technical Report for the Pueblo Viejo mine, Barrick describes this new tailings dam as “one of the largest earth core rockfill dams in the world,” and identifies the need to resettle seven communities as part of the development of the new tailings storage facility – without specifying which communities or providing more details. But people are speaking out.

The Comité Nuevo Renacer was formed by six local communities as a space to articulate their concerns and advocate that Barrick be held accountable for ongoing harms: water contamination, health problems, constant light pollution, layers of dust settling on their homes from daily work on the tailings dam, and contamination from the mine’s processing plants affecting crop health. The six communities are in a valley with the massive El Llagal tailings dam on one side of them and the mine’s processing plant on the other. Given both the daily impacts of mining and the devastation that would be caused should the tailings dam fail, many want to be resettled to an area outside the immediate vicinity of the mine in a way that upholds their human rights and dignity.

While Barrick provides few details about what the future for these communities might look like, the Comité isn’t idle. Following significant international pressure, the Comité succeeded in obtaining a copy of Barrick’s Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) for the planned expansion. The ESIA is a key document that shows how Barrick gauges risk and the criteria the company takes into consideration when evaluating impact, and the way a company conducts an assessment can provide important insight into how the company would respond should a disaster occur.

Together with the National Space for Transparency in the Extractive Industry (Espacio Nacional por la Transparencia de la Industria Extractiva - ENTRE), the Comité has contracted renowned international mining expert Dr. Steven Emerman, who specializes in analyzing risks posed by tailings dams and is a key contributor to “Safety First: Guidelines for Responsible Mine Tailings Management.” Dr. Emerman completed his field visit to the Dominican Republic in July and his report – which will help reveal key project risks and empower communities with information about Barrick’s plans for their future – is expected in the coming weeks.

Unless otherwise indicated, the following photos were taken by MiningWatch Canada’s Research Coordinator Catherine Coumans in November 2022, while in the Dominican Republic at the request of communities affected by Barrick Gold’s Pueblo Viejo mine.

Photo: The El Llagal tailings impoundment at the Pueblo Viejo mine nearing capacity. Communities living directly downstream have long expressed concerns about the safety of the dam, which has been classified as having “extreme” consequences for human life and significant environmental and economic losses should it fail. Failures are taking place with increasing frequency, as extreme shifts in weather patterns caused by climate change can threaten dam stability. The Dominican Republic is particularly vulnerable to hurricanes.

Photo: Children from one of the communities sandwiched between the Pueblo Viejo mine and the tailings impoundment point to tailings pipes and the El Llagal tailings dam behind their houses.

Photo: A mural painted on the headquarters for the Comité Nuevo Renacer says, “Yes to Life! Barrick is death.” The Comité organizes to raise awareness about the impacts of Barrick’s mining activities on their lives and livelihoods and to demand relocation.

Photo: A member of the Comité Nuevo Renacer points to the contaminated Maguaca River that flows along the foot of the tailings dam. Communities denounce that since the water-intensive mine began operating, at least 21 streams have dried up in the area and the mine has severely contaminated the Maguaca River with heavy metals and toxins. Due to this contamination, communities have had to rely on bottled water for drinking and food preparation since 2011.

Photo: Houses in the community of El Naranjo, beside the existing El Llagal tailings impoundment. There is still no clarity on which communities will be resettled if Barrick’s proposal to build a second tailings impoundment goes ahead.

Photo: Three communities were resettled when Barrick first built the El Llagal tailings dam in 2012. Several residents have expressed significant concern about how they were resettled – from communities where they had access to land for cultivation to feed their families and sell, to houses with no land and with no way to pay the expenses that come with the houses. Many of the houses have been abandoned.

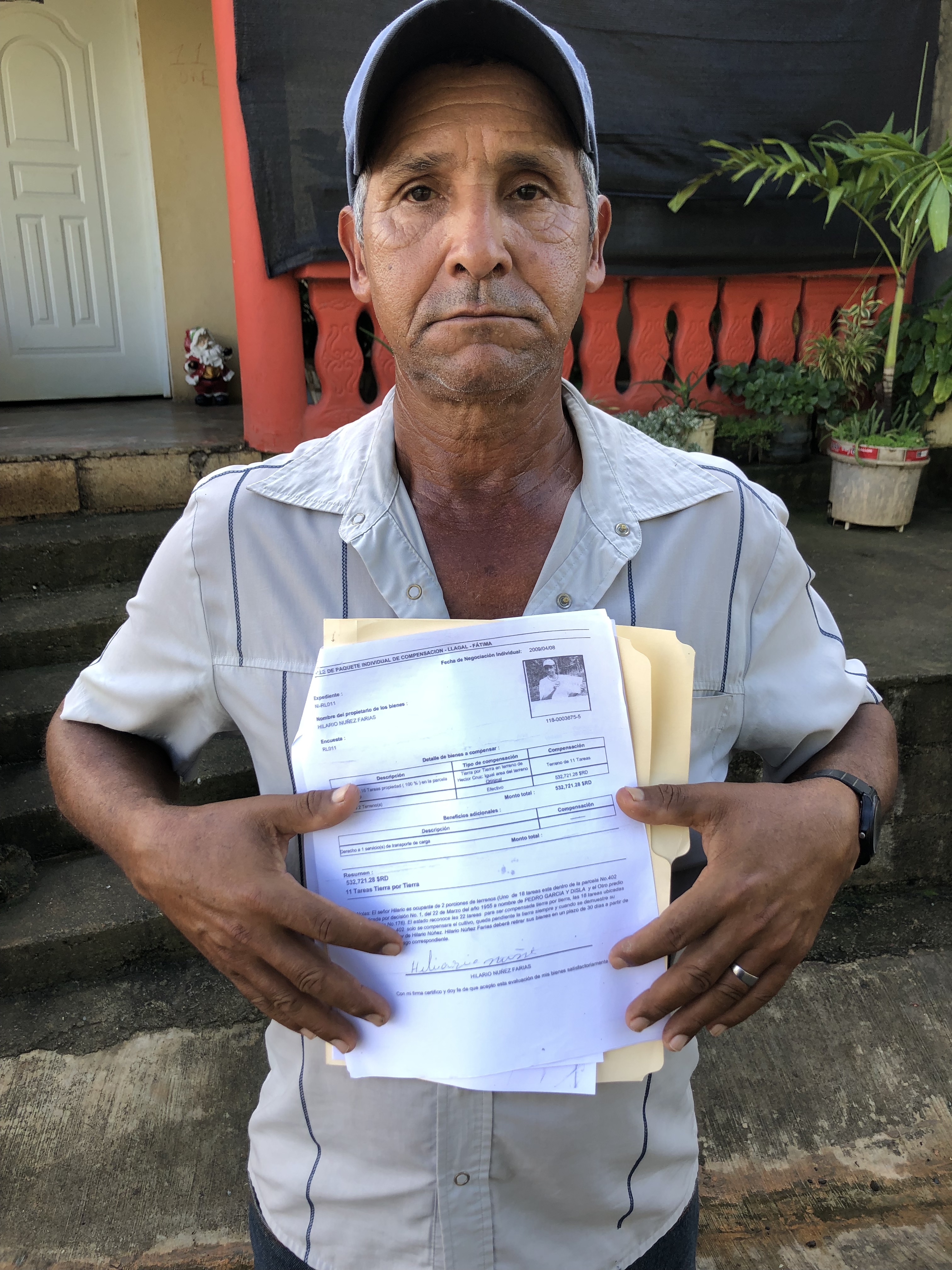

Photo: A farmer who lost land when the El Llagal dam was constructed holds up a signed contract for compensation. To date, him and many others have never received new farmland in another location, been compensated, nor paid for the last they lost. Meanwhile, several communities – including members of the Comité – who continue to feel the daily impacts of mining still advocate to be resettled, but in a manner that they dictate, that is transparent and that upholds their human rights and dignity. Credit: Jan Morrill, Earthworks

Photo: On April 12, 2023, members of ENTRE and the Comité Nuevo Renacer protest outside Barrick Gold’s headquarters in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, as part of a Global Day of Action to #ProtestBarrick. They join other communities affected by Barrick’s operations in Argentina, Tanzania, Papua New Guinea, the Philippines, Pakistan, and the United States in demanding Barrick be held accountable for mining-related harms. Comité spokesperson Pedro Guzmán says, “There hasn’t been any transparency with the communities...The documents [the Environmental Impact Assessment] should be public and the communities should have access to all of them to have clarity around what is going on where we live." Credit: Comité Nuevo Renacer

Photo: Following international pressure, government officials in the Dominican Republic publish Barrick Gold’s Environmental and Social Impact Assessment. Members of the Comité Nuevo Renacer walk near the existing tailings impoundment with Dr. Steven Emerman, an independent mining expert contracted by the Comité and civil society groups to review Barrick’s plans for expansion. The Comité is hopeful this information will better position them to demand transparency from Barrick Gold. Credit: Comité Nuevo Renacer