Ottawa, Ontario, September 10-12, 1999

Innu Nation/MiningWatch Canada

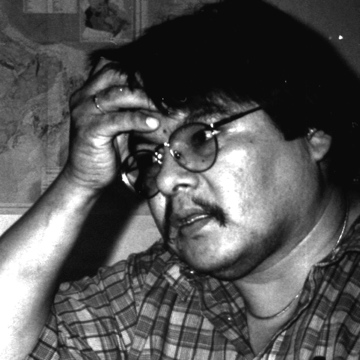

It's quite an honour and privilege to be here today on behalf of the Innu Nation. My name is Daniel Ashini and I live in a community called Sheshatshit, with an Innu population of approximately 1100 to 1200 Innu people, and it's one of the two Innu communities in Labrador which the Innu Nation represents in the political socio-economic arena.

Like I said last night, I'd like to thank you for coming to this gathering, I know many people travelled a great distance to be here today, and many of us sacrificed our time away from home, from family and from friends to be here this weekend. I think you all need to be commended for that effort.

From the introductions we heard today, there's a wide variety of people here, from the grass roots level to political leaders from aboriginal communities to technical people. I'm confident that we can share a lot of experiences in many aspects, many stages of the mining industry that we all have been involved in. I look forward to the next two days of our workshop here.

I myself will be talking to you today about the experiences me and my people have had with industrial development on our land, how we have fought against these developments, and what we have learned from these experiences.

Before I go any further, I would like to thank all the hard work that MiningWatch Canada did to help us put on this workshop.

With few exceptions, Aboriginal people across Canada and around the world are witnessing an incredible change on their lands. Mining and related activities, forestry and hydroelectric developments are just a few of the changes that we have seen, but they are among the most destructive.

It may seem incredible to you, but many Innu people remember a time when we had nothing to do with mining or hydroelectric companies, and once they had settled us in the communities of Sheshashit and Utshimassits, or Davis Inlet, the governments did everything they could to pretend we didn't exist. This was the case only 15 or 20 years ago in my community, and only 6 or 7 years ago in Utshimassits.

Munik, who just spoke to you, is one of these people who remember the Innu as a sovereign people with their own sustainable economy based on hunting and fishing, and gathering. Like Munik, my parents were born in the country, and they lived there for most of their lives, just as their ancestors had for thousands of years. I was part of the first generation to be born in the community and grow up there. I learned the hard way that if you take people away from a life they know and force them into new ways of living, you will help to destroy them as a people. Sheshatshit and Utshimassits were built starting around 1968.

As a people, we have never recognised the jurisdictions that are now so interested in us and our land. We have never signed a treaty, nor ceded a single square inch of our land. In the past these things were not necessary as it was possible for Innu and non-Innu to share the land and its resources. Today we are forced to deal with governments, companies and individuals who are trying to push us aside in a great rush to claim our land as their own for industrial development.

For better or worse, I have a lot of experience in dealing with industrial developments in Ntessinan, our land. I have been arrested and sent to jail several times for protesting the military flight training that takes place on our land. I was also faced with arrest when protesting the proposed Voisey's Bay Nickel mine in a 16 day stand off against 50 or so heavily armed RCMP members. As I'm sure you all know very well, dealing with industrial developments such as mines involves much more than protesting. It also involves participating in environmental assessments, attending co-management meetings, and having big arguments with the governments over things like the definition of consultation.

I have a lot of experience in these matters, but I wish it weren't so. I wish I had never heard of these things that I am going to talk to you about. I wish I could use my time to try to solve the problems of my community instead of always fighting these developments. This takes up a lot of my time, time that I could be spending with my family and friends in the community or in the country.

Our first experience with industrial development was with the Churchill Falls power project. We were never consulted or compensated for this use of our land — in fact, we were never even told that below the dam the Churchill River would be reduced to a trickle, that Churchill Falls would cease to exist, and that our canoes, camps, trap lines, hunting grounds and our ancestors burial sites would be drowned forever by the Smallwood Reservoir. I visited a site at the edge of the reservoir with two archaeologists and my uncle, and saw that the reservoir had eroded a hillside and uncovered some Innu graves. I had personally heard of these stories from people in our communities before but they never did really sink in until this direct experience. It was very sad to see that those graves had been destroyed, and completely unforgivable in my opinion.

From our experience with the Churchill Falls power project, we learned that if the government is allowed to do whatever it wants, we would get screwed. We learned that we had to raise our voices effectively in order to be heard. Unfortunately, we find that many government bureaucrats are poor listeners and it has taken them about 30 years to understand what we thought was a simple message: you have to ask us first if you want to use our land. As one of the many people who continuously delivers this message, I can say that while it requires a tremendous amount of sacrifice, delivering this message has been a great experience. It is very encouraging and positive to see the conviction our people have proudly and bravely shown in protecting our land. Seeing the community empowerment that results from this has given me a great deal of strength as a leader.

We faced many more developments on our land over the years, including the proposed Brinco Uranium mine near Makkovik which thankfully did not go into operation for economic reasons, forestry, hunting and fishing camps and Iron ore mining in Wabush-Labrador City and Schefferville.

The next major industrial development came in the mid 1980s in the form of a proposed NATO base, which would have included military low level flying, live ammunition and bombing ranges. Low level flying is when NATO fighter jets are flown at almost supersonic speeds close to the ground, training to avoid radar detection. Officially the jets are supposed to fly no lower than 100 metres above the ground, but many of our people have seen the jets flying just above the tree tops, skimming the lakes and the rivers that our people depend on for their subsistence.

These jets leave a trail of pollution and a noise so loud and sudden that it has caused people to tip over in their canoes, it has frightened children so badly that they have panicked, run away and got lost. There is a lot of confusion after the jets fly over and things often get knocked off the stove by people panicking, which can give children serious burns. There is documented evidence in Germany that low level flying causes nightmares and other anxiety attacks in children, and they can't sleep properly. There have been no studies done on the effects of low level flying on the Innu, and I don't think I have to tell you what the effects of a live bombing range would be on our land and our people.

We fought low level flying in a variety of ways: we protested at the Canadian Forces Base in Goose Bay, at the Department of National Defence headquarters here in Ottawa and at the Volkel Air Force Base in Holland, we used the media to publicise our situation, and we made the government conduct an environmental assessment of the proposed NATO base. We found protesting and using the media to be very effective in getting our voices heard. Unfortunately, the environmental assessment was not as effective. The problem there was that the government controlled the process, and was being manipulated with interference by the Department of National Defence. To complicate matters, the project was scaled down from a full NATO base, when NATO decided they didn't need a base, to military low level flight training only. We found the assessment to be biased in favour of the Department of National Defence. We eventually boycotted the environmental assessment because of this and other reasons.

Soon after our experience with low level flying, we faced the extension of a logging road right next to our community. With construction of the road already underway we presented the workers with an eviction notice and set up our tents there to ensure that once they left they did not return. We had a meeting with Provincial officials, but that meeting didn't succeed in resolving anything. After that we demanded a meeting with then Premier Clyde Wells. We met with Clyde Wells and were successful in preventing the road from being extended.

Our next big struggle came in 1994, when the Voisey's Bay Nickel deposit was discovered by two prospectors looking for diamonds. When we realised that the exploration company and governments were ignoring our rights once again, we repeated our strategy of protesting that we learned from military low level flying. The protests were effective and made the company and government realise that we were serious when we said there would be no mine without our consent.

I'd like to briefly describe the protests, because I was involved in both protests. The first one occurred shortly after a mineral exploration camp had been established and drilling had already started at Voisey's Bay. After intense community meetings in Utshimassits, it was decided that we had to re-assert governance over our land, and give a strong message to the mining industry and to the governments. Shortly after that meeting a large convoy of snowmobiles left this tiny community in the coldest days of winter, in February of 1995. Men, women and children travelled together. Some people experienced mechanical problems along the way, and without any complaint did their repairs in bare hands in this very cold weather, in temperatures that went as low as -40 to -50.

We arrived at Voisey's Bay and handed the camp manager an eviction notice. We then waited awhile for a response from the company. They informed us that they had permits for the work they were doing, permits from a government who'd never been provided jurisdiction by the rightful owners, the Innu and Inuit, to provide these permits. We then began disrupting the drilling activity they were conducting. This took place all day, with the men, women and children working together. Drilling was disrupted and stopped while the company officials were confused and tried to figure out what to do next. Over the next few days we set up camps, heated only by wood stoves, right next to the exploration camp, and watched while RCMP members in great numbers were flown in many helicopter trips from Goose Bay, Labrador.

After a number of protests we had at the exploration camp and a number of incidents between our people and the RCMP members, Diamond Field Resources, who had provided the contract for this exploration, intervened, and called for a meeting between Innu Nation officials, Band Council officials and board members of Diamond Field Resources. This happened after 16 days of our people spending their time at Voisey's Bay, protecting their interest, protecting their rights, and trying to give a message to the company that we were serious. The meeting that had been called by Diamond Field Resources I believe was the first step in any exploration that should have taken place with the Innu before any exploration activity commenced. Unfortunately, the company and governments ignored the Innu and the Innu were forced to take action. This was the start of Impact Benefit negotiations with the company directly with the Innu Nation.

The second protest took place in the summer of 1997, and this was a joint action with the Inuit of Labrador. It took place again at Voisey's Bay. People travelled from Sheshatshit by bush plane, and people from Davis Inlet travelled by boat to Nain, or directly to Anaktalak Bay. This action was taken jointly by the Innu and Inuit because the company had been given permits to proceed with the construction of a temporary road from the coast to where the mineral discovery had been made, and the construction of a temporary airstrip, so the company could get involved in what they called advanced exploration, underground exploration. The company had been provided with the permits, even though there was an environmental assessment which was supposed to take place. We argued that the company was trying to split the project, that the road and airstrip that they were going to build were essentially going to be used for the mine once the mining got started, and the construction should not be allowed to take place.

We proceeded with a court case which unfortunately we lost. We appealed, and while the appeal was taking place the company had already started with the construction of the road. Therefore the Innu and the Inuit decided to stop the work that was being undertaken by the company while we were waiting for a response from the court of appeal. While we were at Anaktalak Bay, where the Voisey's Bay camp was, we heard through communication with our legal council that we succeeded in the court of appeal. I'll talk a little more about this in a few minutes. Anyway, these are a couple protests that many of us were involved in, including Munik, staff people from the Innu Nation and many people from both communities.

We made a mistake in the first protest, I believe. In an effort to prevent the RCMP from coming in and arresting us, we blocked the frozen lake used as a runway. This is what the people of Utshimassits did when they kicked the judge and RCMP out of their community, and it worked very effectively for them. However, this time the RCMP came in by helicopter, and as we all know helicopters can land almost anywhere. Unfortunately, reporters could not come in to report on the protest because airplanes could not land, and we heard that the helicopter company was prevented from bringing reporters in by the exploration companies. Apparently, Archean Resources and Diamond Field Resources were threatening to terminate their contracts with the helicopter companies if reporters were brought in. We did not get a lot of media coverage from this protest, and this meant that it wasn't as effective as it could have been.

At this point I'd like to say that we do not protest just because we like protesting, or for the sake of protesting. We do it when we feel that we have run out of other options, and we feel that there is no other way to get people or governments to listen to us.

In 1995 we put together a task force on mining, and held community consultations in both communities to hear what our people had to say about mining and the mineral exploration companies that were taking over our land. The task force came back to us with several key recommendations, including:

- Land rights should be resolved before any mining goes ahead.

- The company is moving too rapidly and should move at a pace that allows for proper consultation and planning. After all, the minerals aren't going anywhere.

- The Innu Nation should proceed to negotiate an impact benefit agreement, but with extreme caution given the level of opposition and concern within the communities.

- The company should be prepared to go beyond the requirements of the governments' environmental assessment process. It should accept a broad definition of environmental impacts, one that examines past, present and future implications for both natural and human environments.

- The company should be committed to an ongoing process of defining a relationship of partnership with the Innu Nation, one which allows for a meaningful, not just token, role for Innu in decision making regarding a mining development at Voisey's Bay.

- The Innu Nation should continue to view protests as a viable and potential strategy to address the issue of mining developments on Innu land.

The report is called Between a Rock and a Hard Place, and I think many of you have been provided with copies to take back to your communities. The report has been very useful, because it has given us a very clear mandate on how to deal with the company and governments. For example, when we say something like "the communities will not accept this project without a land rights agreement and an IBA," they know we are telling the truth because it can be backed up by this document.

As I said before, when Voisey's Bay Nickel Company (VBNC) tried to build a temporary airstrip and a road at the site, we used the courts to try and stop them. In our opinion this infrastructure was a part of the project and its construction without undergoing environmental assessment would constitute splitting of the project. We were opposed to this because we were trying to get a comprehensive environmental assessment. The governments didn't seem to share our concerns and issued permits to allow VBNC to go ahead with the construction.

We lost our first case but won at the Supreme Court of Newfoundland Court of Appeal, and were successful in stopping the construction this way. In their ruling, Judges Marshall, Steel and Green had some heartening words for us. They said that:

"In this province, as elsewhere, society has been left to grapple with the deleterious, and at times tragic, effects of unbridled development on the health and security of its residents and upon the environment. The recent experience of the devastation of the fishery through over-exploitation bears stark witness to the consequences of the impact which the pace of humankind's activities, especially those driven by economic forces, can have.

As important as are environmental considerations, sight cannot be lost of the economic and social benefits that flow from the production of these resources... Nevertheless, they cannot be allowed to control the agenda without regard to competing environmental interests."

After the court ruling, we negotiated a memorandum of understanding with the Labrador Inuit Association, the Federal Government and the Provincial Government. This document was key in the positive outcome of the environmental assessment. It allowed us to participate in the selection of panel members, and to set the guidelines the panel would have to follow. I believe that the MOU was a key first step in getting the recommendations that land rights agreements and IBAs would have to be settled before the project could proceed. But perhaps most importantly, it was probably the first MOU in Canada between aboriginal groups and the governments where no treaty exists. In signing the MOU, the governments essentially said that they recognised the authority of the Innu government, and we were given the same authority over the process as they had.

Funding was a serious issue for us in our participation in the environmental assessment. Our original plan was to conduct a concurrent assessment, one that would use Innu traditional knowledge to predict the impacts of the proposed mine. Unfortunately, we didn't have enough money to carry this out. We did receive $80,000 in intervenor funding from the Canadian Environmental Assessment Agency to pay for experts to review VBNC's studies and the Environmental Impact Statement, and to make presentations at the public hearings. Unfortunately this fell well short of what we required. While we worked closely with the Labrador Inuit Association to make sure we weren't doing the same work twice, we did have to prioritise a few issues for the environmental assessment which meant that there were technical issues we simply could not address. If we go through an environmental assessment process for the proposed Lower Churchill project, we will have to ensure that we have adequate funding to participate fully.

I think that our participation in the public hearings was very effective, and the second key step in getting the recommendations on land rights agreements and IBAs. People were very clear in getting their message across to the panel, and they spoke from their hearts. Because of the community consultation, visits to the site and community meetings, people were clear on which issues were important to put forward to the panel.

People were not ashamed to talk about the problems that exist in both communities and how they have suffered from them. Even though it is difficult to talk about these things, our people have done a lot of hard work to make public the social and cultural misery that we live in. It is heart wrenching to talk about alcoholism, physical and sexual abuse, suicides and how children sniff gas every night, but we felt it was necessary to let people know what is happening in our communities in order to begin addressing our problems.

The panel members were very moved when people told them their life stories and were impressed by people's knowledge of the land. The fact that public hearings were held in the communities helped the panel to understand our living conditions and to put what we were saying into its proper context. This way the panel was able to see what our communities were like and were able to see what people were talking about when they said they were afraid of the social and cultural impacts of the mine, and how these impacts could very well push many people over the edge.

The panel recommended that the mine could go ahead, but not without land rights negotiations being concluded and IBAs being settled. There were also 105 other recommendations, but the key recommendations as far as the Innu were concerned were the ones on the conclusion of our land rights agreement and IBAs. They would have meant that the Innu would be able to consent to the mine through the signing of these agreements, that the Innu Nation would be a recognised government that would have meaningful input into many aspects of the mine, and that the people would have been able to negotiate fair compensation for what they were giving up.

Unfortunately, many Innu are forgetting about the importance of these recommendations in their rush to embrace new business opportunities. Many Innu are being corrupted by non-Innu who are encouraging them to form joint venture business partnerships to get contracts at the mine. These individuals have been blinded by greed, self-interest and the promise of money. This creates a serious conflict for the Innu Nation and the Band Councils because it pits the private businessmen against our community owned development corporation, which is called Innu Economic Development. Needless to say, VBNC and the governments are happy to encourage these private businessmen.

So what we have here is a situation where before the mine has even opened it has created a serious conflict in our communities. We have friends and relatives fighting amongst themselves, and the community spirit that the Band Councils and Innu Nation worked so hard at achieving is being lost.

If the businessmen are successful in their effort to undermine community efforts, I fear we will have dealt our culture a very serious blow. The collectivity of the Innu people and our tradition of sharing will be lost, and this move will play into the hands of the government and individualism. We will be one step closer to assimilation. We can only hope that common sense will prevail.

In any case, both governments rejected the recommendations on land rights and IBAs in their responses to the panel report. They said that they could not give the Innu a veto over the mine, they could not legally compel the company to conclude an IBA with us, and that the mine could proceed without these agreements. The governments offered no replacement to these recommendations that would have helped mitigate social and cultural impacts of the project other than an assurance that they would continue to negotiate, and that the company should continue to negotiate an IBA with us. We are in the process of taking the governments to court over their decision to allow the project to proceed without land rights or IBAs being in place.

We feel very strongly that we have the right to consent to the mine. We have the right to say no and the right to say yes. If we say yes, there is a responsibility that comes with that which is a very huge burden. This is the responsibility of recognising that a part of our land will be destroyed forever and we must make sure that it isn't destroyed needlessly. If we say no to the mine, and all the opportunities that come with it, we need to understand what we're working towards as a community for our future and our children's future and not just know what we're working against.

As a nation, we now find ourselves with the prospect of having an operating mine on our land in the near future. If this is to be the case, then we are entering into an area of great uncertainty. We have little faith in the predictions of the company as to what will happen to the land and to our communities once the mine opens. I am looking forward to today's and tomorrow's discussions to hear about your own experiences in dealing with mining companies, and how your communities have dealt with the impacts they bring. By sharing with us your stories you will make us all stronger in dealing with the mining industry. I'll also be happy to answer any questions you might have about the Innu Nation's experience with mining to date.

Tshinishkumiten, thank you very much.