(Guest blog by Paul Filteau) In June of 1981, a company executive from Eldorado had flown in to Uranium City, Saskatchewan to announce closure of the Beaverlodge Mine, the main employer. It was completely unexpected. It was a tight knit and prosperous community. The 3000 residents were stunned!

In February, 1983, I flew in a small bush plane to Uranium City. Regular air service to the community had discontinued. En route, we dropped down flying over expansive sand dunes south of Lake Athabaska, then across the frozen lake. Normally, the pilot would tip his wings, a “hello” to dog teams crossing the lake; however, this time there were none. As the plane descended, children could be seen jumping in the water from a dock. The melting ice had receded from the shoreline. It was the first time “El Nino” had come this far inland. Indeed, at 59 degrees north latitude hen temperatures often plunged to 40 below, the sudden winter warming was a new phenomenon.

When I met with them, representatives of the two hundred or so citizens that remained were bushed, desperate and out of money. No-one had ever anticipated having to wait for the ice to refreeze in the middle of winter. Transport trucks sat loaded with their possessions and the drivers hoping to get back over to Fort Chipewyan at the west end of the lake. They never did.

There was work for miners who had relocated to Saskatoon or Prince Albert and would fly back north to work at uranium mines near Key, Cluff or Rabbit Lakes. Many originally came from Northern Ontario and returned to their home communities. One had to wonder why the Saskatchewan Government closed down Uranium City. It had been a well-serviced town for the families, both indigenous and non-native alike. Instead, they were forced to depart without furniture, homes or businesses. Despite the cost, a few managed to barge their possessions out in the spring.

For others who chose to remain in the north, it was a different story. Many of the indigenous people had already returned to their ancestral communities, most to Fond du Lac or Stony Rapids and Wollaston Lake. Unfortunately, these communities were struggling with problems of their own. There was neither the housing nor water or power infrastructure to accommodate their existing populations, let alone a flood of new families. Their children were born and had grown up in Uranium City. Most did not speak Dene.

Meanwhile in Uranium City, the remaining people - some non-native but mostly Metis, others Dene and a few Cree - were reluctant to move to Prince Albert or Saskatoon where they experienced discrimination. Despite the restaurant, store and the few remaining services that would soon be shutting down, about 75 residents decided they would try and hold on. Today about 50 of them are still living there. Disturbingly, about the same as the number of former uranium mines abandoned in the area.

Unfortunately, the plight of former mining communities, the hazards of associated radioactive mine waste and and the health of an older generation of miners and their families have been largely forgotten. If you search in Google under Gordon Edwards, you can see in a video where he talks about the dangers uranium mining for Mining Watch Canada.

Recently, I asked Janice Martell, heading up the McIntyre Powder Project, if she had been able to locate any miners from Uranium City. I thought the aluminum dust had been blown into miners' lungs until the mine closure in 1981. Many of them were only in their twenties. She replied, “It is sadly not surprising to see how many deaths are related to uranium mining. The few miners and families that I speak to who were from Uranium City all tell me that everyone they know from the mining days is dead. Several of the Elliot Lake guys said the same thing -'all of my friends are gone.' ”

The bogus claim of the industry was that aluminum dust protected the miners' lungs from silicosis. In reality, the aluminum deposited in nerve ganglia leading to a syndrome of diseases, cancers, early dementia and death. Their lungs blackened with aluminum dust confused compensation claims to save the companies and the compensation boards money. The miners in miserable health, many in poverty, died prematurely.

There is a cultural and geographic divide in the nuclear industry. Even though they produce the most toxic waste known to man, the nuclear establishment down at the reactors, highly educated and extremely well paid, likes to whitewash itself as clean and even green. They work in “Laboratories” and in public wear spotless overalls and white hats. After being coached by public relations experts, sometimes they fly north professing great love for the mosquitoes and reassuring us that all their radioactive waste is eternally safe. “Trust us! We're the answer to climate change.” A little ratepayers cash helps to spread the goodwill.

Paradoxically, they disavow their relationship to their mining and milling cousins, the people who get the ore out of the ground and then do the refining. They leave the carbon footprint. Ironically, the nuclear experts then like to bury radioactive fuel rods back underground, in chambers created by miners. No dumps here. The word is “repository.” In time, like the mines, they would like to forget about it. Out of sight – out of mind. The history of the north.

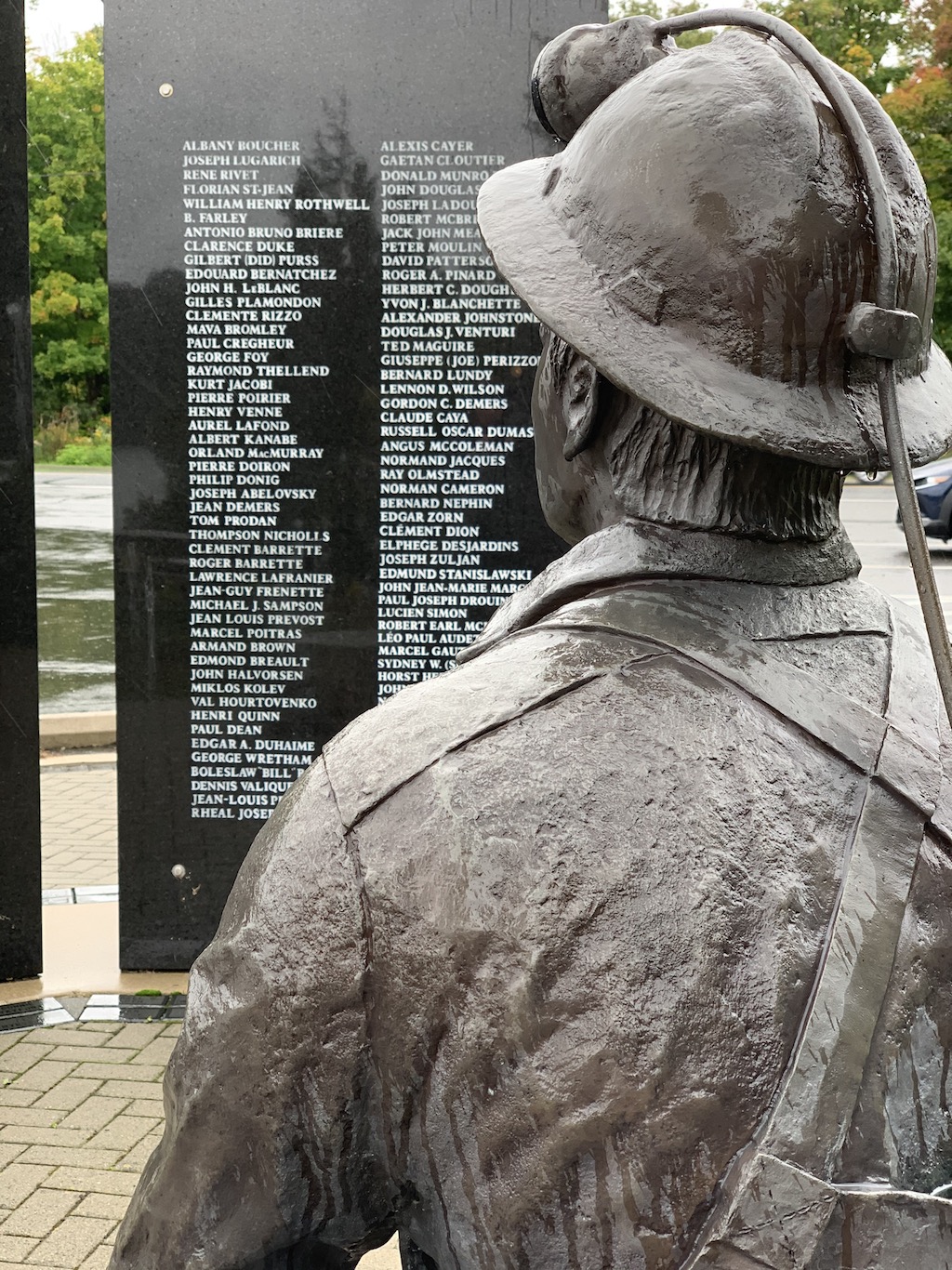

The article entitled ”Memorial to Elliot Lake's uranium miners now complete” in Northern Ontario Business, May 26, 2021 and unveiling video is available online. It was welcome to see the third and final piece of a trilogy sculpted by artist Laura Brown Breetvelt acknowledging the contribution of miners. Likely, a number of the miners listed on the tablets had also spent some time in Uranium City.

The author, Paul Filteau, originally from Kirkland Lake flew to Uranium City in February, 1983 for the Employment Development Branch, Government of Canada to assist unemployed workers in the applications for job creation projects. At present he is very concerned with the siting of a deep nuclear repository for high level nuclear waste, west of Ignace in Northern Ontario.