“The scandal is what’s legal.” – Edward Snowden

The massive leak of secret banking information tagged “The Panama Papers” has made a lot of waves in the weeks since its contents started being made public, and they were renewed this week with the release of a searchable database of leaked material.

Those waves may yet prove strong enough to overcome the sandbag redoubts created by banks and wealth individuals and corporations (who are also legally people, right?) to protect their wealth from marauding tax collectors.

If they do, it will be because the public decides that it has finally had enough of those who are pleased to benefit from public services and public goods (like mineral deposits) – but will go to extraordinary lengths to avoid contributing to those public services.

The leak of client information from the Panama law firm Mossack Fonseca shines a very bright light on the unfairness of an international system that creates shrouds of secrecy around the movement of money and facilitates the spread of tax evasion (illegal) and tax avoidance (legal, but reprehensible). The more people find out, the less they like it.

Where’s Canada?

Some Canadians – both individuals and corporates – do appear in the database, but not many. Initially, CBC said it would not publish the names of some 350 Canadians exposed through the leaks, not out of concern for their reputations, but because they weren’t famous enough. CBC did confirm that they included mining and oil and gas executives, lawyers, and even known fraudsters.

ICIJ – the International Coalition of Investigative Journalists, who received the leaked documents and controlled the media coverage – did publish a partial database of leaked information just this week. They are revealing only names and locations, and will only release other details from the leaked documents (e-mails, transactions etc.) as they see fit.

One Canadian company that did jump out of the database was Ivanhoe Mines, led by mining promoter Robert Friedland. The leaks show the structure that Ivanhoe used to operate in Burma (Myanmar) for many years in violation of international sanctions against that country’s military dictatorship, and how Friedland eventually sold the property to Rio Tinto.

Bearing in mind that Mossack Fonseca is only one of a number of law firms that specialise in secret accounts – and far from the largest, apparently – even this huge data leak still only represents a small portion of the world of secret offshore investment. Even so, it seems curious that Canada and the US are so underrepresented. There are good explanations, however – as the Tax Justice Network has pointed out, there are good reasons that US money would not hide in Panama, including the fact that states like Delaware and Nevada are major, and more accessible, secrecy jurisdictions.

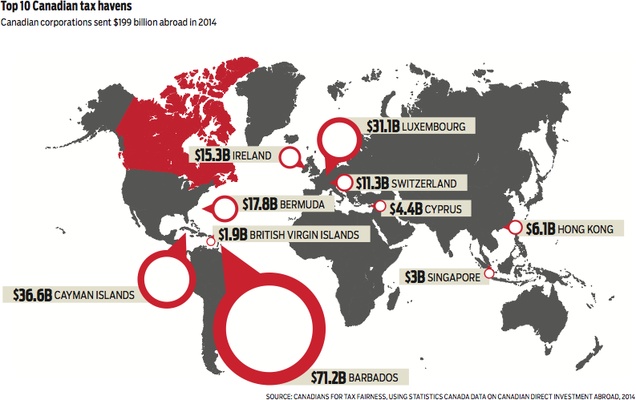

Panama is not the main destination for Canadian dollars seeking to avoid community service work, either. Business in Vancouver’s Jen St. Denis explains nicely how Barbados gets the lion’s share, followed by the Cayman Islands and Luxembourg. Canadians for Tax Fairness notes that the amounts are growing rapidly, now over $40 billion a year, and lately more has been going to the Cayman Islands (see graphic).

Canada does have a significant interest in Panama, however – in mining. First Quantum Minerals’ multibillion dollar “Cobre Panama” is the only operating mine, but several more are at different stages of development. Their investments are protected by the Canada-Panama Free Trade Agreement, which, like most modern free trade agreements, has precious little to do with free trade – or in this case, any trade at all – and more to do with investment protection.

We were one of few groups to raise the alarm when the Canada-Panama FTA was debated in Parliament in 2012. We warned that Panamanians, especially the peasant farmers and indigenous peoples with the most to lose, would lose any possibility of pressing their government to put their interests ahead of international investors, thanks to the agreement’s NAFTA-like investment protection provisions.

There was a link to financial secrecy and corruption, too, of course. Todd Tucker of Public Citizen’s Global Trade Watch warned that the pact “would give new rights to the Government of Panama, and to the hundreds of thousands of offshore corporations located there, to challenge Canadian anti-tax-haven initiatives outside of the Canadian judicial system.”

Justin Trudeau and the Liberals joined the Conservative government of the day in supporting ratification of the deal; the NDP, Bloc Québécois, and Greens opposed it.

Beyond Panama

Pressure to end secrecy around “beneficial ownership” (the actual owners of these accounts and businesses) and to impose transparency on payments to governments are vital steps toward exposing corruption in the hope that once exposed, it will be too embarrassing to continue. However, the crucial issue in the mining sector (as opposed to, say narcotics trafficking) is corporations’ ability to move money around to take advantage of the most favourable legal tax applications. There is certainly fraud and corruption, but it is actually less important than what is pillaged legally or semi-legally, and what corporations legally avoid contributing to the countries where they actually operate – and incur massive public liabilities, for damage to workers’ health, water supplies, etc.

Global Financial Integrity outlines illicit financial flows in a fairly easy to understand way, estimating that in 2013 $1.1 trillion left developing countries. GFI says this is a conservative estimate, which is quite an understatement as it doesn’t include huge but even harder to quantify flows in money laundering or mispricing of services. GFI has found that illicit flows out of Africa are probably significantly greater than development aid and foreign direct investment combined.

Crucially, complex subsidiary structures also allow corporations to avoid liability. Nevsun, for example, is being sued over allegations that the company was complicit in the Eritrean government’s use of conscripted labour and other human rights abuses at the company’s Bisha mine. As Business in Vancouver recently noted:

Nevsun…owns the Bisha mine in Eritrea indirectly through a complex link of subsidiaries. Nevsun Resources (Canada) owns 100% of Nevsun (Barbados) Holdings Ltd., which owns Nevsun Africa (Barbados) Ltd., which owns 100% of Nevsun Resources (Eritrea) Ltd., which owns 60% of the Bisha Mine Co. The Eritrean National Mining Corp. owns the remaining 40% of the Bisha Mine Co.

This isn’t even secret; like Nevsun, many companies lay out their subsidiary structures in their annual reports and regulatory filings. But they don’t publicise the financial flows between those subsidiaries, which is where profits are shifted from one shell company to another to avoid taxation – and even show losses to take advantage of subsidies and tax credits.

What needs to happen is as simple as it is politically difficult, given the confluence of powerful interests with a lot of money at stake. Bruce Livesey has outlined in the National Observer how difficult it will be to change this.

Full transparency is essential, revealing the actual owners of secret accounts, but it is only a first step. There needs to be a legitimacy test, to ensure that corporate subsidiaries have a legitimate business purpose or economically substantial role. Canada should simply not allow corporations to route money through shell companies or “mailbox” subsidiaries in tax havens and secrecy jurisdictions. Other than tax avoidance and evasion – or money laundering – there is no legitimate reason for it. NDP MP Murray Rankin tried to introduce such a test to the Income Tax Act with a private member’s bill (C-621) in 2014, but why not apply it to corporations?

As the Tax Justice Network commented with respect to individuals, “We are unaware of any legitimate reason as to why individuals need to incorporate companies in secrecy jurisdictions. It is now time for that practice to end.”